Oral Health

Key Points

Primary teeth usually erupt between 6-12 months of age, while adult teeth begin erupting between ages 5 and 7 years and finish by ages 13 to 14 years.

Encourage families to establish a dental home by 12 months of age (and as early as 6 months of age) and monitor for regular dental visits. Patients with special health care needs may need a multidisciplinary oral health care team and more frequent visits.

Common issues in children with special health care needs include:

- Build-up of calculus resulting in increased gingivitis and risk for periodontal disease.

- Dental caries.

- Dental crowding.

- Malocclusion.

- Enamel hypoplasia.

- Oral aversion and behavior problems.

- Anomalies in tooth development, size, shape, eruption, and arch formation.

- Bruxism and wear facets (areas worn down from teeth rubbing together).

- Fracture of teeth or trauma.

Minor dental procedures usually do not require prophylactic antibiotics. However, invasive procedures involving manipulation of gingival tissue, periapical region of the tooth, perforation of the oral mucosa, or procedures done on children at especially high risk for infection (e.g., certain cardiac conditions, compromised immunity, or prosthetic materials in the body) can warrant antibiotic prophylaxis. Amoxicillin is typically the drug of choice.

Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) are major sources of coverage for pediatric dental care. For those who do not have dental insurance, the PCP should provide information for a local, publicly funded, or charity-care dental office.

Guidelines

Krol DM, Whelan K.

Maintaining and Improving the Oral Health of Young Children.

Pediatrics.

2023;151(1).

PubMed abstract

Clark MB, Keels MA, Slayton RL.

Fluoride use in caries prevention in the primary care setting.

Pediatrics.

2020;146(6).

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Oral Health Problems in CYSHCN

Children and youth with special health care needs may face oral health challenges related to:

- Inability to perform self-care

- Medical devices that impact oral health

- Medications that have adverse effects on oral health

- Seizures

- ADHD/autism/ developmental delays

- Gingival hyperplasia

- Overcrowding of teeth or malocclusion

- Oral aversions from previous medical procedures or sensory defensiveness

- Xerostomia (dry mouth)

- Dietary factors

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease or vomiting

- Enamel hypoplasia (particularly in premature infants)

- Bruxism

- Lack of access to dentists with appropriate training in treating children and adolescents with complex health care needs [American: 2018]

Physical Examination

Physical examination should include visual inspection of the mouth for:

- Candidiasis (thrush)

- Dental caries (tooth decay)/white spot lesions

- Gingivitis/gum disease (inflamed, red, or bleeding gums)

- Abscesses

- Tongue-tie or ankyloglossia

- Tooth discoloration

- Tongue plaques

- Intraoral ulcerations (canker sores)

- Herpes simplex virus lesions (intra and extraoral cold sores)

- Chipped teeth

- Jaw pain

- Halitosis

- Tumors

- Plaque or calculus build-up

- Presence of prior fillings

- Abnormal tooth eruption

- Oral habits (pacifier or digit sucking)

Signs of normal and abnormal tooth eruption

- Primary teeth usually erupt between 6-12 months of age, typically beginning with the lower anterior incisors and complete eruption between 25-33 months of age.

- Although some infants develop natal or neonatal teeth, this type of eruption is uncommon.

- Delayed tooth eruption in children >12 months old may result from a medical condition and should be evaluated. Referral is warranted if a child has no teeth by 18 months of age. [American: 2017]

- Permanent teeth typically erupt between ages 5 and 7 years with the 1st molars or lower central incisors and finish eruption, except the third molar, by age 13 years old.

For more detail, see Dental Growth and Development (American Dental Association).

Treatment & Management

The primary care clinician regularly evaluates and treats common conditions affecting the oral cavity, including the tongue, cheeks, and lips. Primary care clinicians should also provide anticipatory guidance for oral health, including establishing a dental home, diet, home care routines, and the use of fluoride toothpaste. Guidance can be found at Dental and Oral Health Screening.

Pediatric and general dentists provide care for most conditions affecting dentition (teeth) and gums. Encourage families to establish a dental home by 12 months of age (and as early as 6 months of age) and monitor for regular dental visits. [American: 2005] A dental home is an ongoing relationship between the dentist and patient that addresses anticipatory guidance and preventative, acute, and comprehensive oral health. [American: 2023]

A pediatric dentist has special training in meeting the needs of infants, children, and adolescents, particularly children with special health care needs who may have complex oral health challenges or have difficulty cooperating with an oral exam or procedures. Children and youth with special health care needs will likely need a pediatric dentist who can perform moderate to full sedation for evaluations and procedures, and the primary care provider should provide an appropriate referral. The primary care clinician can assist parents with identifying a dentist covered through their insurance plan. (See Services below.)

Children with complex medical conditions or special health care needs may have trouble with regular toothbrushing at home. Modifications can help them maintain good oral hygiene (e.g., electric toothbrushes, modified toothbrushes, chlorhexidine mouth rinses, or sprays). [Levy: 2018] In some cases where caregivers do not seek care or assistance, dental neglect may be present. Primary care providers need to assess these situations and determine if a report to child protective services is needed when true neglect is diagnosed. [Fisher-Owens: 2017]

Condition-Specific Guidance

- Prosthetic cardiac valve

- Previous infective endocarditis

- Congenital heart disease

(CHD) with one of the following:

- Unrepaired cyanotic CHD, including palliative shunts and conduits

- Completely repaired congenital heart defect with prosthetic material or device, whether placed by surgery or by catheter intervention, during the first six months after the procedure

- Repaired CHD with residual defects at the site or adjacent to the site of a prosthetic patch or prosthetic device

- Cardiac transplantation recipients who develop cardiac valvulopathy

- Immune suppression (e.g., HIV/AIDS, SCIDS, neutropenia, undergoing chemotherapy or chronic use of steroids, or stem cell or solid organ transplant)

- Autoimmune conditions (e.g., juvenile arthritis or lupus)

- Sickle cell anemia or diabetes

- Asplenia

- Head and neck radiation

- Bisphosphonate use

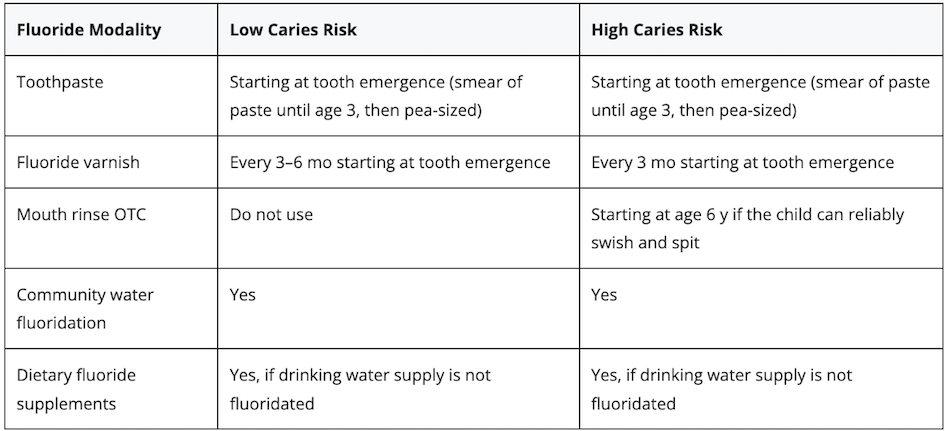

Topical Fluoride

Fluoride acts in 3 important ways to prevent caries: 1) by strengthening enamel, 2) by remineralizing enamel, and 3) by affecting microbial metabolism and reducing acid production by cariogenic bacteria. Systemic, fluoride in water or by supplement, and topical fluoride applications are the primary sources of fluoride. [American: 2021]

Prophylactic Antibiotics

Patients usually do not need prophylactic antibiotics for minor dental procedures, such as routine anesthetic injections through non-infected tissue, dental radiographs, placement of removable prosthodontic or orthodontic appliances or brackets, shedding of primary teeth, and bleeding from trauma to the lips or oral mucosa. [Otto: 2021] [Wilson: 2021] Remember that most systemic infections in these patients are NOT due to dental procedures. Good oral hygiene is the primary prevention tool.

Consider prescribing prophylactic antibiotics for certain invasive dental procedures (manipulation of the gingival tissue or the peri-apical tooth area or perforation of the oral mucosa) to patients at the highest risk of a distant site infection in the body. [Otto: 2021] [Wilson: 2021] The primary care clinician should discuss with the family the potential benefits and risks (including developing resistant bacteria) of prophylactic antibiotics for patients with any of the conditions described in the section above.

The 2021 Endocarditis Prophylaxis Wallet Card (AHA) provides a table of antibiotic prophylactic regimens for dental procedures by situation, agent, and dose. Recommendations and further information about population, procedures, specific antibiotics, dosing, and timing are detailed in the 2007 American Heart Association guidelines. [Wilson: 2021]

Referrals and Services

Medicaid

(see UT providers

[10]) and CHIP, State Children's Health Insur Prog

(see UT providers

[4])

Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) are

major sources of coverage for pediatric dental care. States define what

constitutes “medically necessary” oral health services for Medicaid recipients.

[U.S.: 2017] Some state Medicaid programs

provide enhanced payments when a modifier (EP) is applied to the claim for

specific oral health services during well-child visits. For those families

without dental insurance, the primary care clinician should provide information

for a local, publicly funded, or charity-care dental office.

The Affordable Care Act expanded insurance coverage of pediatric

oral health services; however, there are still children who cannot access oral

health care. Other services include:

CPT Coding

99188, application of topical fluoride varnish by a physician or other qualified health care professional

Resources

Information & Support

For Professionals

Open Wide: Oral Health Training for Health Professionals (OHRC)

Four modules about tooth decay, risk factors, prevention, and anticipatory guidance; National Maternal and Child Oral Health

Resource Center, Georgetown University.

The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry: Oral Health Policies & Recommendations (American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry)

A collection of recommendations and policies pertaining to pediatric dentistry.

Protecting All Children's Teeth (PACT): A Pediatric Oral Health Training Program (AAP)

Educational materials and resources to assist physicians in training medical students and residents in oral health; American

Academy of Pediatrics.

For Parents and Patients

Campaign for Dental Health (AAP)

Created to ensure that people of all ages have access to the most effective, affordable, and equitable way to protect teeth

from decay; American Academy of Pediatrics.

Top Problems in Your Mouth Slideshow (WebMD)

Images and descriptions of common oral health problems.

Tools

Oral Health Pocket Guide (Bright Futures)

Anticipatory guidance information, risk assessment guides, a fluoride supplement chart, and tools for improving the oral health

of children from before birth to young adulthood.

Oral Health Practice Tools (AAP)

Many tools in Spanish and English to help with setting up your practice to include oral health, applying fluoride varnish,

performing a risk assessment and an oral exam, helping families find a dental home, and providing patient education; American

Academy of Pediatrics.

Services for Patients & Families in Utah (UT)

| Service Categories | # of providers* in: | UT | NW | Other states (3) (show) | | NM | NV | RI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHIP, State Children's Health Insur Prog | 4 | 2 | ||||||

| General Dentistry | 93 | 1 | 12 | 13 | 47 | |||

| Healthcare, Dental | 150 | 2 | 16 | 33 | 66 | |||

| Medicaid | 10 | 3 | 8 | 25 | 6 | |||

| Oral/Maxillofacial Surgery | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Pediatric Dentistry | 50 | 2 | 6 | 24 | 54 | |||

For services not listed above, browse our Services categories or search our database.

* number of provider listings may vary by how states categorize services, whether providers are listed by organization or individual, how services are organized in the state, and other factors; Nationwide (NW) providers are generally limited to web-based services, provider locator services, and organizations that serve children from across the nation.

Authors & Reviewers

| Author: | Tyler T Miller, MD |

| Senior Author: | Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAP |

| Reviewer: | Jeri Bullock, DDS |

| 2023: update: Tyler T Miller, MDA; Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAPSA |

| 2020: first version: Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAPA; Jeri Bullock, DDSR |

Page Bibliography

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry.

Management of Dental Patients with Special Health Care Needs.

Pediatr Dent.

2018;40(6):237-242.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry.

Definition of dental home. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry.

Chicago: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry;

2023.

https://www.aapd.org/media/policies_guidelines/d_dentalhome.pdf

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry.

Antibiotic prophylaxis for dental patients at risk for infection.

The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry..

2022;Chicago, Ill:500-6.

/ Full Text

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry.

Policy on the management of patients with cleft lip/palate and other craniofacial anomalies. The Reference Manual of Pediatric

Dentistry.

Chicago: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry;

2023.

https://www.aapd.org/media/policies_guidelines/e_cleftlip.pdf

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry.

Policy on use of fluoride. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry.

Chicago: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry.;

2021.

https://www.aapd.org/media/policies_guidelines/p_fluorideuse.pdf

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry Council on Clinical Affairs.

Policy on the dental home.

Pediatr Dent.

2005;27(7 Reference):18-9.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

American Academy of Pediatrics.

Protecting All Children's Teeth (PACT): A Pediatric Oral Health Training Program.

(2017)

https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/O.... Accessed on Dec. 2023.

Clark MB, Keels MA, Slayton RL.

Fluoride use in caries prevention in the primary care setting.

Pediatrics.

2020;146(6).

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Clinical Affairs Committee.

Guideline on Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Dental Patients at Risk for Infection.

Pediatr Dent.

2016;38(6):328-333.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Fisher-Owens SA, Lukefahr JL, Tate AR.

Oral and Dental Aspects of Child Abuse and Neglect.

Pediatrics.

2017;140(2).

PubMed abstract

Krol DM, Whelan K.

Maintaining and Improving the Oral Health of Young Children.

Pediatrics.

2023;151(1).

PubMed abstract

Levy H.

General dentistry for children with cerebral palsy.

In bbook: Cerebral Palsy (pp1-40).

2018.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Lewis CW, Jacob LS, Lehmann CU.

The Primary Care Pediatrician and the Care of Children With Cleft Lip and/or Cleft Palate.

Pediatrics.

2017;139(5).

PubMed abstract

Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd, Gentile F, Jneid H, Krieger EV, Mack M, McLeod C, O'Gara PT,

Rigolin VH, Sundt TM 3rd, Thompson A, Toly C.

2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American

College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Circulation.

2021;143(5):e35-e71.

PubMed abstract

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

Does Medicaid Cover Dental Care.

(2017)

https://www.hhs.gov/answers/medicare-and-medicaid/does-medicaid-cover-.... Accessed on Dec. 2023.

Wilson WR, Gewitz M, Lockhart PB, Bolger AF, DeSimone DC, Kazi DS, Couper DJ, Beaton A, Kilmartin C, Miro JM, Sable C, Jackson

MA, Baddour LM.

Prevention of Viridans Group Streptococcal Infective Endocarditis: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association.

Circulation.

2021;143(20):e963-e978.

PubMed abstract

Get More Help in Utah

Get More Help in Utah